To learn more about racism in America, I read two books written by black men. The first one was Tears We Cannot Stop, by Michael Eric Dyson. The second was Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Dyson wrote his book to white America. Coates wrote his book to his fifteen-year old son. Both men wrote about the suffering, despair, and fear that result from racism and about the terror of police brutality.

Two perspectives…

Inside the covers of Dyson’s book are the words, “how we can make it through the long night of despair…to the bright day of hope.” Dyson, a professor at Georgetown University and an ordained minister, wrote his book as a sermon to White America because we need to hear the blunt, honest truth about the consequences of the “original sin” of slavery. Although the “sermon” was tough to read, Dyson softened his message by referring to the white reader as “beloved.”

Coates, a national correspondent for The Atlantic, wrote about growing up in fear in Baltimore. He went to Howard University and read extensively about black history trying to understand the divide between the black life he knew and the white American Dream.

When Coates heard his son crying after learning that Michael Brown’s killers would go free, he did not reassure him that everything would be okay. He told him “that this is your country, that this is your world, and you must find some way to live within the all of it.”

Somewhere out there beyond the firmament, past the asteroid belt, there were other worlds where children did not regularly fear for their bodies.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me

As a man of faith, Dyson believes in the power of redemption. Coates does not believe in God and never believed that a just God is on his side.

Throughout his book, Coates frequently referenced black bodies, starting with the opening line: “Son, Last Sunday the host of a popular news show asked me what it meant to lose my body.” Later, he wrote that the question of his own life was how to live “within a black body, within a country lost in the Dream.” “White America,” he wrote, “is a syndicate arrayed to protect its exclusive power to dominate and control our bodies.”

I was puzzled about why Coates kept referring to black bodies. People of color aren’t just bodies – they have hearts and souls just as I do! Then I thought about America’s long history of owning and controlling black bodies. Black bodies were treated like property, as less than human. Black bodies were segregated from white bodies. White people controlled where blacks could work and go to school. White people controlled where black people could live and eat. Even today, many whites act like black bodies are disposable. We see again and again that whites have the power to slay black bodies with impunity. Coates was telling his son, your black body belongs to you. You will also have to learn how to live in this country within a black body.

Inventing Whiteness

Dyson wrote about the invention of “whiteness.” Whiteness is not genetic; it is a social “inheritance.” Whiteness is privileged in America not because there is a legitimate reason to be privileged but because people with white skin have made it so. Whiteness took various ethnic identities – German, Italian, Jewish, etc. and built them up into another identity. Whiteness is willfully ignorant of black life. Whiteness is a defensive shield that keeps whites from facing the realities that blacks have always known. Whiteness keeps whites from being empathetic – from putting themselves in another’s shoes.

Paraphrasing James Baldwin, Coates frequently referred to people with white skin as “people who think they are white” or “people who want to be white.” Coates wrote that “race is the child of racism not the father.” There have always been differences in skin color and hair. Believing that skin color can be used to organize social hierarchies is the idea of “people who have been brought up hopelessly, tragically, deceitfully, to believe that they are white.”

The Five Stages of White Grief

Dyson wrote that whites have been grieving for years over the loss of our dominance and preferential position in history. He described what he called five stages of white grief:

- Pleading ignorance about black life and culture

- Denying any responsibility for racism

- Appropriating black culture, history, identities

- Revising racial history

- Diluting or minimizing racism

Many whites do react with anger and denial as in the stages of grief at the loss of a loved one (anger, denial, bargaining, depression, acceptance). However, the responses of whites to racial issues are not stages or phases that whites will get over once we work through anger and denial. I wish that it were so.

Much of what Dyson wrote about white grief are examples of white fragility. Whites are defensive and protective of the status quo. Many whites refuse to admit the reality of black life in America. We promote a racially blind version of history. We forget or “disremember” our horrible past and refuse to acknowledge the ongoing consequences. We claim to be colorblind. We try to minimize the effects of racism by saying that bad things happen to everyone.

Terror of policing

Both writers explained, through experience, why black people are terrified of the police. Dyson told a story about his son, an anesthesiologist, who was stopped by a policeman while driving a rental car with his five-year old in the back seat. The cop told him it was illegal to drive and talk on a cell phone at the same time. Dyson’s son had not been talking on the phone; it had fallen on the floor when he turned the corner. The more he tried to politely insist that he had not broken the law, the more upset the cop became. He placed his hand on his gun. He asked Dyson’s son if he was stupid. The cop said, I should take you to jail and I would, but I have no place to put a child. He gave him a ticket and a warning and said if I ever see you again, I will take you to jail. Imagine facing this hostility and knowing you could have died because you drove while being black.

Sadly, stories like this are not unusual. This summer, I read about Elijah McClain, a 23-year old black man from Aurora, Colorado, who was reported as suspicious because he was waving his arms, dancing while walking to the store. The cops placed him in a chokehold. He tried to explain, I don’t do that stuff. I don’t even kill filies. A paramedic injected him with ketamine to subdue him. Elijah McClain had a heart attack and died within a week. Twenty-three years old.

I can’t breathe. I have my ID right here. My name is Elijah McClain. That’s my house. I was just going home. I’m an introvert. I’m just different. That’s all. I’m so sorry. I have no gun. I don’t do that stuff. I don’t do any fighting. Why are you attacking me? I don’t even kill flies! I don’t eat meat! But I don’t judge people, I don’t judge people who do eat meat. Forgive me. All I was trying to do was become better. I will do it. I will do anything. Sacrifice my identity, I’ll do it. You all are phenomenal. You are beautiful and I love you. Try to forgive me. I’m a mood Gemini. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. Ow, that really hurt. You are all very strong.

Many whites deflect when the subjects of police brutality or discrimination come up. They bring up black on black crime, disregarding the prevalence of white on white crime. They say, they shouldn’t have run. They should have cooperated. But as Dyson wrote, no matter what we do, the cops come for us. It doesn’t matter if we’re polite and tame, we’re seen as a menace and a threat. Blackness is viewed as criminal and as less than human.

This breaks my heart.

The Plague of White Innocence

We are afraid that when the tears begin to flow, we cannot stop them.

Michael Eric Dyson

Whites do not like to be challenged on racial issues. When blacks bring injustice to our attention, we often react with indifference or deafening silence. Or we blame the victims of injustice. Dyson urged White America to let go of our whiteness and find our humanity. We should accept accountability for our collective capacity for terror. We have to accept responsibility for accepting a privileged way of life that comes at the expense of people of color. We should surrender our innocence and face the truth with all the discomfort it brings.

At the end of his book, Coates told his son, “I do not believe that we can stop them, Samori, because they must ultimately stop themselves.” “Hope for them. Pray for them, if you are so moved.”

Lord, I pray for white America. I pray that we will listen and respond with empathy and compassion to the voices of our beloved black brothers and sisters and that we will stop defending a way of life that is unjust. I pray that we will acknowledge our collective responsibility for the sin of racism. Amen.

****

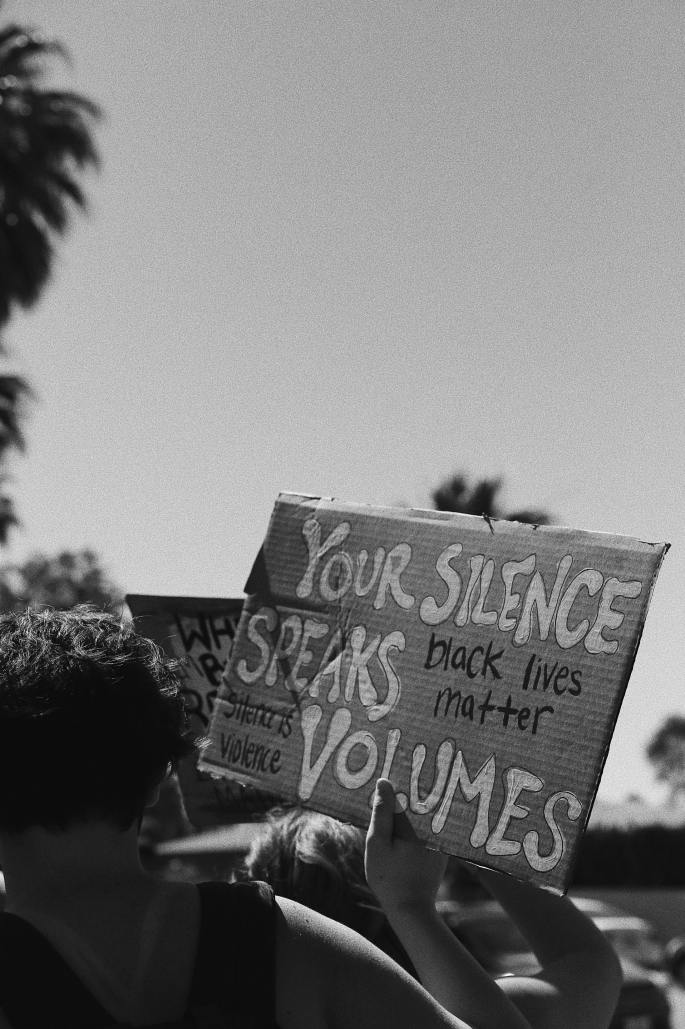

Photo by Taylor Simpson on Unsplash